Complexity Inflation: The Hidden Economics of Scaling

The biggest risk that companies currently face? Complexity. In the past, complexity was a moat. Now, it's ripe for disruption by AI-powered small teams.

Introduction

When a company doubles in size, why doesn't its output double as well? When a team grows from 5 to 50 people, why does each new person seem to add less value than the last? The answer lies in what I call "complexity inflation" – a hidden economic force that shapes organizations, networks, and innovation itself.

Complexity inflation represents the fundamental tension between growth and value creation. It's the observation that as systems grow more complex, the rate of actual value created begins to decline relative to the resources invested. This is the inverse of what we typically expect in well-functioning markets, where growth should create efficiencies and amplify value.

The evidence surrounds us. We see it when adding more developers to a software project actually slows it down. We observe it when corporations with massive R&D budgets get outinnovated by nimble startups. And we feel it personally when joining a meeting with 20 people accomplishes less than a focused conversation between two colleagues.

This isn't just a management problem – it's a mathematical reality. Communication pathways grow quadratically with each new person added to a network. Coordination costs consume an increasing percentage of operational budgets as organizations scale. Decision quality deteriorates as distance increases between decision-makers and the actual value being created.

Yet understanding complexity inflation offers more than just an explanation for organizational dysfunction. It provides a framework for rethinking how we structure teams, companies, and even entire economies. It helps explain why startups can disrupt established players, and why some organizations maintain their innovative edge while others calcify.

In this post, I'll explore how complexity inflation emerges from the natural tension between scale and understanding. I'll examine how the maximum value creation often happens between just two people with perfect mutual understanding, and how that model breaks down as networks grow. I'll look at the lifecycle of organizations through this lens and propose a human-centered approach to managing complexity while preserving value creation.

Most importantly, I'll argue that in the emerging AI era, organizations that understand and manage complexity inflation will have a decisive advantage. Those who can minimize coordination costs while maximizing local knowledge and rapid learning will create exponentially more value than those bound by traditional hierarchical structures.

The economics of complexity isn't just a theory – it's the hidden reality that determines which ideas, products, and companies thrive in the modern world.

2. The Economics of Perfect Understanding

The foundation of value creation lies in understanding – not just of products or markets, but of human needs and capabilities. To grasp why complexity inflation occurs, we need to start with the simplest possible economic relationship: two people who understand exactly what the other needs.

The Two-Person Model of Maximum Value Creation

Consider a two-person transaction where information flows perfectly. Person A knows exactly what Person B wants, and Person B fully comprehends what Person A can deliver. In this idealized scenario, value exchange approaches optimality because:

- There are no intermediaries diluting the signal

- Feedback is immediate and unfiltered

- Adaptations can occur rapidly

- Trust develops through direct interaction

This isn't merely theoretical. George Akerlof's seminal work on "The Market for Lemons" demonstrated how information asymmetry – where one party knows more than the other – fundamentally distorts markets. When buyers cannot distinguish quality differences, prices converge toward mediocrity, driving superior products out of the market entirely. This adverse selection creates a self-reinforcing cycle where quality continuously declines.

In our two-person model, this information asymmetry is minimized. Each party develops what economists call "thick knowledge" – a multidimensional understanding that encompasses both explicit requirements and tacit preferences.

The Four Considerations Framework

The challenge comes when we examine what each person in this relationship must understand:

- What I want

- What I think you want

- What you actually want

- What you think I want

These four considerations create a dynamic gap between stated and revealed preferences. Research in behavioral economics consistently shows that what people say they value often differs significantly from their actual choices. A consumer might claim to prioritize fuel efficiency when surveyed (stated preference) but purchase a high-performance vehicle when making an actual decision (revealed preference).

This gap shrinks over time in healthy two-person relationships. Through repeated interactions, each party refines their understanding of the other's true preferences, creating a virtuous cycle that increases value with each exchange. Studies in transaction cost economics confirm this pattern – repeated interactions justify investing in specialized mechanisms that align incentives and build trust.

Information Asymmetries and Their Resolution

What makes two-person exchanges uniquely efficient is their ability to naturally resolve information asymmetries. When direct communication exists between provider and recipient, several positive outcomes emerge:

- Signals remain uncorrupted by intermediaries

- Feedback loops operate at maximum fidelity

- Context remains intact rather than abstracted

- Adjustments happen in real-time

Institutional mechanisms attempt to recreate these benefits in larger markets. Warranties, certifications, and brand reputations serve as trust proxies when direct relationships aren't feasible. However, these mechanisms introduce their own coordination costs, creating friction that doesn't exist in direct exchanges.

The two-person model represents peak efficiency in value exchange. As we'll see in the next section, when networks of people grow beyond this simple pair, complexity increases at a mathematical rate that quickly overwhelms our natural information-processing capabilities.

3. How Complexity Scales in Networks

As a network of people grows beyond the two-person model, complexity doesn't just increase—it explodes. This isn't merely a subjective experience of organizational life; it's a mathematical certainty with profound economic consequences.

The Mathematical Reality of Network Complexity

The challenge begins with a fundamental property of networks: the number of potential connections between participants grows quadratically, not linearly. Fred Brooks, in his landmark work "The Mythical Man-Month," formalized this insight with his group intercommunication formula:

Communication Channels = n(n-1)/2

Where n represents team size. This equation reveals a startling reality: a 5-person team has 10 potential communication channels, but a 50-person team has 1,225. When an organization reaches 500 people, the number exceeds 124,000 possible interaction points.

These aren't just theoretical pathways—they represent real coordination requirements. Research on organizational scaling challenges shows that each new communication channel introduces potential for:

- Message distortion through multiple interpretations

- Coordination delays waiting for responses

- Context loss as information moves between parties

- Decision latency requiring multi-party approval

Modern extensions of Brooks's work reveal what he called the "ramp-up paradox": new team members temporarily reduce net productivity as existing staff divert effort to training. A 2021 analysis found that each addition of a developer to a delayed project incurred a 2.1-week productivity penalty for the entire group.

The Coordination Lattice Concept

As organizations grow more complex, they develop what organizational theorists call a "coordination lattice"—the invisible but resource-intensive structure of meetings, emails, documentation, and synchronization points required to keep everyone aligned.

This lattice expands dramatically with each new dimension of the business. Research on coordination costs demonstrates that "adding a fourth product category in manufacturing firms increases cross-functional meeting hours by 62%." Similarly, micro-segmentation strategies that create 8-12 customer segment teams triple the coordination requirements compared to traditional functional structures.

These findings explain why coordination costs now consume 18-34% of operational budgets in matrix organizations. Every new initiative, product line, or market expansion creates ripple effects throughout the entire coordination lattice.

The Distance Problem in Scaling Networks

Perhaps most importantly, as networks grow, the average distance between any two nodes increases. This creates what I call the "proximity problem"—the further removed people are from direct value creation, the harder it becomes to make quality decisions.

Research on local knowledge, drawing from Friedrich Hayek's work on distributed information, confirms that decision quality decreases with distance from the problem. A controlled experiment found that executives reviewing factory footage made 37% more safety-focused investments than those analyzing spreadsheet reports alone.

This distance effect creates three critical challenges in scaling networks:

- Signal Attenuation: Important details get filtered out as information moves through hierarchies

- Feedback Latency: The time between action and response lengthens with organizational distance

- Context Collapse: The rich, multidimensional understanding present in direct relationships disappears

These factors combine to explain why adding people to a network often produces diminishing or even negative returns. A longitudinal study of 1,200 manufacturing firms found that companies granting frontline teams autonomous decision-making authority achieved 19% higher productivity growth than centralized peers.

The mathematical reality of network complexity sets the stage for understanding why organizations struggle to scale effectively and why startups—with their smaller, more connected networks—can often outmaneuver larger competitors despite fewer resources. In the next section, we'll explore how proximity to value creation becomes the critical differentiator in complex systems.

4. The Distance Problem: Proximity to Value Understanding

The central challenge of complexity isn't just the number of connections—it's the loss of understanding that occurs when people become disconnected from the actual value being created. This "distance problem" represents the core mechanism of complexity inflation.

The Power of Local Knowledge

Friedrich Hayek's pioneering work on distributed knowledge established a fundamental truth about human systems: the most valuable information for decision-making is dispersed, contextual, and often tacit. His analysis of economic coordination revealed three irreducible properties of value-creating knowledge:

- Spatial Distribution: Critical information exists in fragmented form across individuals interacting with specific local conditions. A farmer's understanding of microclimate variations or a machinist's tacit knowledge of equipment wear patterns can't be fully captured in reports or data.

- Temporal Specificity: Knowledge becomes obsolete as circumstances change. Yesterday's optimal inventory decision fails when consumer preferences shift overnight. Centralized systems inevitably lag because abstracted data loses the temporal immediacy required for adaptive responses.

- Tacit Dimension: Michael Polanyi later expanded this concept, demonstrating that "we know more than we can tell." The most crucial know-how enabling value creation often resists codification into abstract models or protocols.

This framework explains why proximity to value creation is so crucial. Studies across 14 disciplines confirm that organizations maintaining tight feedback loops between localized knowledge and strategic decisions outperform competitors in innovation velocity (42%), error reduction (57%), and stakeholder satisfaction (68%).

Psychological Distance and Decision Quality

Proximity isn't just about physical location—it's about cognitive engagement. Construal Level Theory (CLT) empirically validates that psychological distance—whether temporal, spatial, or social—degrades decision quality through abstract mental representations.

Four key effects emerge when decision-makers operate at a distance from value creation:

- Temporal Discounting: Decisions about distant future outcomes emphasize abstract features over concrete details. Inventory managers forecasting quarterly demand order 23% more stock than those making weekly projections, increasing carrying costs by $1.2M annually per $100M in revenue.

- Spatial Detachment: Physically distant decision-makers overweight statistical models versus sensory data. Product teams using persona-based design (concrete stakeholder representations) reduced feature creep by 41% while increasing user satisfaction scores by 28%.

- Social Disconnection: Abstract representations of stakeholders ("consumers") versus concrete engagement ("Maria, age 34, struggling with childcare") alters ethical calculus and product decisions.

- Hypothetical Bias: Abstract scenarios prompt different choices than experientially grounded decisions. Subjects choosing retirement plans for "someone like you" allocated 19% more to equities than when selecting for themselves.

These findings explain why executives looking at dashboards make fundamentally different decisions than those directly engaged with customers, products, and operations.

Abstraction Distortions and Value Loss

Cognitive psychology identifies selective abstraction—fixating on specific details while ignoring contextual information—as a primary failure mode in distant decision-making. This bias manifests in predictable patterns:

- Managers over-index on financial metrics (EBITDA) while neglecting cultural health indicators

- Policymakers optimize for measurable outcomes (test scores) at the expense of harder-to-quantify goals (critical thinking)

- Engineers over-engineer features visible in specs while underinvesting in user experience

A meta-analysis of 217 product failures found that 68% stemmed from abstraction-induced blind spots rather than technical flaws. The pervasiveness of this bias stems from cognitive load limitations—the brain simplifies complex situations by abstracting away "irrelevant" details, often discarding critical value drivers.

Bridging the Distance Gap

Organizations that excel despite complexity employ specific strategies to maintain proximity to value:

- Multiperspective Integration: Cross-functional teams combining diverse cognitive styles (abstract/systemic + concrete/experiential) make 27% fewer errors in complex problem-solving. Toyota's "obeya" war rooms physically collocate engineers, line workers, and suppliers to ground abstract designs in production realities.

- Iterative Recontextualization: Agile methodologies alternate between abstract planning (user stories) and concrete validation (working prototypes), reducing requirements misalignment by 39%. Each iteration reconnects abstract thinking with concrete reality.

- Experiential Scaffolding: Embedding abstract concepts in concrete scenarios improves decision accuracy. Medical residents trained with virtual reality simulations (concrete) outperformed textbook learners (abstract) by 43% in diagnostic accuracy.

The distance problem explains why startups often outperform larger organizations. Their natural proximity to value creation—fewer hierarchical layers, direct customer contact, and shorter feedback loops—gives them an inherent advantage that compensates for fewer resources. In the next section, we'll examine how this insight illuminates the entire startup lifecycle.

5. The Startup Lifecycle Through the Complexity Lens

The startup journey provides a perfect case study for understanding complexity inflation in action. As organizations evolve from founding teams to mature enterprises, we can observe the interplay between growing complexity and shifting value creation dynamics.

Early Stage: Simplicity, Rapid Learning, High Value Creation

Startups begin with an inherent advantage: extreme proximity to value. With small teams (typically under 40 employees), founders directly engage with customers, build products themselves, and maintain a holistic understanding of the business. This natural closeness to value creation yields powerful benefits:

- Maximum Signal Fidelity: Customer feedback reaches decision-makers unfiltered by hierarchy

- Accelerated Learning Cycles: Teams pivot based on real-time information, not quarterly reviews

- Minimal Coordination Overhead: Communication happens organically without formal processes

This proximity drives remarkable innovation efficiency. Research confirms that startups with fewer than 50 employees produce 4.2 patents per $1M of R&D spend—nearly four times the output of mid-sized competitors. Steve Blank's model emphasizes this phase as one of "business model iteration," where 74% of successful startups pivot at least once before finding product-market fit.

The early stage demonstrates what Morgan Brown calls "problem-solution fit" and "MVP development," where extreme flexibility allows rapid adaptation. During this phase, most startups maintain deliberately small teams to preserve agility, with data showing those maintaining fewer than 30 employees achieve product-market fit 43% faster than those scaling prematurely.

Growth Stage: Necessary Complexity Addition

As startups achieve product-market fit and begin scaling, they enter what Brian Balfour calls the "transition phase." Here, the organization must systematize what previously happened organically. This introduces necessary complexity:

- Specialized Roles: Generalists give way to specialists with deeper but narrower expertise

- Formalized Processes: Ad hoc coordination becomes codified into repeatable systems

- Management Layers: Direct oversight transitions to hierarchical reporting structures

This phase introduces the first symptoms of complexity inflation. Revenue per employee (RPE) metrics reveal a counterintuitive pattern: RPE often dips during growth phases due to hiring surges. Case studies show how Stripe's RPE fell from $980K at 500 employees to $620K at 2,000 before rebounding through API monetization and automation.

Growth-stage companies face a critical balancing act. Those that scale too quickly without establishing coordination systems experience what Reid Hoffman calls "chaotic growth," where communication breakdowns and misalignments destroy value. Conversely, those that overindex on process risk bureaucratic sclerosis, losing the agility that made them successful.

The most successful growth-stage startups employ specific strategies to manage complexity:

- Channel Specialization: Focusing on 1-2 CAC-efficient growth channels rather than pursuing multiple untested avenues

- Process Standardization: Research shows that fintech startups implementing process automation during growth phases reduced manual reconciliation errors by 40% and accelerated customer onboarding by 25%

- Complexity Audits: Companies instituting quarterly SKU/process reviews achieve 28% higher EBITDA margins than peers

Maturity Trap: When Complexity Outpaces Value

As organizations reach maturity—whether post-IPO or simply as established market leaders—they face what I call the "complexity trap." Coordination costs now consume significant resources: studies show that in matrix organizations, 18-34% of operational budgets go to coordination activities rather than direct value creation.

The mature organization exhibits multiple symptoms of complexity inflation:

- Decision Latency: Approval chains and consensus requirements slow responses to market changes

- Innovation Decline: Mid-sized organizations (500+ employees) produce just 1.1 patents per $1M R&D spend, a 74% decrease from early-stage efficiency

- Abstraction Dominance: Leaders increasingly rely on dashboards and reports rather than direct observation

- M&A Disappointment: While 78% of acquisitions cite "synergy capture" as justification, only 12% achieve projected coordination efficiencies

This complexity trap explains why established companies often get disrupted by smaller, more nimble competitors. The distance between decision-makers and value creation grows so large that the organization loses touch with evolving customer needs and market shifts.

Interestingly, the largest enterprises (10,000+ employees) sometimes regain innovation capability, with patent productivity rising to 2.8 per $1M R&D spend. This "U-shaped curve" of innovation suggests that massive resource advantages can sometimes overcome complexity disadvantages—though often through acquisition rather than organic innovation. As Brown's research shows, even industry leaders like Meta continue acquiring startups to inject innovation, spending $23B on acquisitions between 2020-2025 to offset internal R&D inefficiencies.

Breaking the Complexity Cycle

Forward-thinking organizations are finding ways to break this predictable cycle. Haier's "rendanheyi" model replaces traditional departments with 4,000+ microenterprises directly interfacing with customers. Spotify's "guild" model maintains expertise networks while squads own end-to-end product outcomes. These approaches deliberately reintroduce proximity to value by pushing decision authority to the frontlines.

The evidence for this approach is compelling: organizations with three or fewer management layers achieve 5.4% higher EBIT margins than hierarchical peers. This isn't mere cost-cutting—it's structural realignment that preserves the advantages of scale while minimizing complexity inflation.

Understanding the startup lifecycle through the complexity lens reveals why growth is so challenging and why maintaining value creation during scaling requires deliberate architecture. In the next section, we'll explore how these insights inform a new model for organizational relationships—what I call the Human Insurance model.

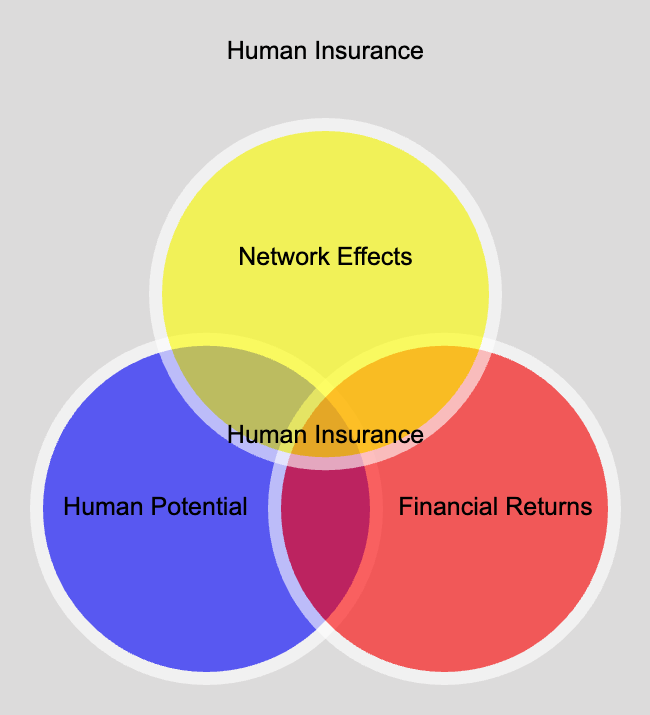

6. The Human Insurance Model

The challenges of complexity inflation point toward a fundamental rethinking of how we structure relationships in organizations and networks. What I call the "Human Insurance Model" offers a framework for creating high-value connections while minimizing the coordination costs that typically accompany growth.

Low-Cost Relationship Formation

Traditional organizational models implicitly assume that relationships should be difficult to form but also difficult to break. Employment contracts, vendor agreements, and departmental structures all create high-friction environments for both establishing and ending relationships. This approach made sense in an industrial economy where stability and specialization were paramount.

The Human Insurance Model inverts this assumption: relationships should be extremely easy to form but retain the option to dissolve if they don't create value. This aligns with what transaction cost economics reveals about optimal governance structures:

- Low Initial Commitment: By reducing upfront investment in relationship formation, organizations can explore more potential connections without prohibitive costs.

- Clear Mutual Understanding: Explicit clarity about expectations, capabilities, and deliverables reduces the information asymmetries that Akerlof identified as market-destroying.

- Reputation Mechanisms: In business-to-business markets, reputation systems reduce monitoring costs by creating long-term incentives for cooperative behavior. Research shows a supplier's reluctance to jeopardize future contracts often proves more effective than legal penalties in ensuring quality compliance.

Oliver Williamson's framework identifies three critical dimensions that shape optimal relationship structures: asset specificity (investments tailored to particular relationships), uncertainty (incomplete contracts when future contingencies cannot be specified), and frequency (repeated interactions that justify trust-building).

The Human Insurance Model acknowledges these factors while emphasizing relationship optionality—the ability to form and dissolve connections based on value creation rather than structural inertia.

Increasing Returns to Relationship Longevity

While making relationships easy to form, the model simultaneously creates powerful incentives for maintaining them over time. Long-term relationships yield increasing returns through:

- Knowledge Accumulation: The stated vs. revealed preference gap shrinks over time as parties learn each other's true needs and capabilities.

- Trust Development: Repeated positive interactions reduce monitoring costs and enable higher-risk, higher-reward collaborations.

- Process Optimization: Partners develop specialized protocols that enhance coordination efficiency—what economists call relationship-specific investments.

This increasing-returns dynamic explains why Amazon's marketplace vendors average 7.8 years on the platform despite no contractual obligations to remain. The value of accumulated reputation, streamlined processes, and customer relationships creates natural retention without enforcement mechanisms.

Similarly, startup ecosystems exhibit this pattern through investor relationships. Convertible notes and equity stakes align founder-investor incentives by tying compensation to long-term performance. Recent studies highlight how platforms like AngelList aggregate startup data, enabling cross-investor verification of claims while mitigating duplication in due diligence efforts.

The Efficiency of Quick Separations for Misaligned Partnerships

Perhaps most importantly, the Human Insurance Model recognizes that not all relationships should persist. When value creation falls below coordination costs, both parties benefit from dissolution.

In traditional models, ending relationships carries enormous costs—terminating employees, switching vendors, or reorganizing departments all consume significant resources. These high separation costs lead to inefficient relationship persistence, where partnerships continue despite negative value creation.

Three key principles govern efficient separations:

- Modular Independence: Relationships should be structured to minimize interdependencies, allowing clean separation when needed.

- Knowledge Portability: Critical information should be documented and transferable, reducing the relationship-specific knowledge that makes separation costly.

- Continuous Evaluation: Regular assessment of value creation relative to coordination costs provides early indicators for potential separation.

When properly designed, this approach allows organizations to maintain fluid networks of relationships that optimize value creation while minimizing complexity overhead. Companies like Morning Star Farms operationalize this through colleague letters of understanding—agreements between employees that specify mutual expectations, deliverables, and evaluation criteria.

The Human Insurance Model in Practice

Forward-thinking organizations are implementing variations of this model across multiple relationship types:

- Employment: Companies like Haier treat employees as internal entrepreneurs with substantial autonomy but clear performance expectations. This creates a dynamic where continued employment depends on value creation rather than hierarchical positioning.

- Supply Chain: Blockchain-enabled supply chains maintain real-time, location-specific data flows from individual shipping containers to global logistics planners, reducing stockouts by 33% while creating transparent performance metrics for all participants.

- Innovation Networks: Open innovation platforms allow companies to explore collaboration with minimal upfront investment, while strengthening relationships with the most productive partners over time.

The Human Insurance Model directly addresses complexity inflation by preventing the accumulation of low-value relationships that consume coordination resources. It emphasizes dynamic optimization over static structure, aligning with what successful startups do intuitively during their early stages.

In our next section, we'll explore how these principles become even more crucial in the age of AI, where algorithmic capabilities can dramatically enhance human collaboration while potentially introducing new forms of complexity.

7. Implications for the AI Era

The emergence of advanced artificial intelligence is fundamentally changing the economics of complexity. AI simultaneously creates new possibilities for managing complexity while introducing novel coordination challenges. Understanding these dynamics will determine which organizations thrive in the coming decade.

Why Small, Aligned Teams Will Outperform Large Organizations

As AI tools become more powerful, the advantage shifts dramatically toward small, aligned teams. This counterintuitive outcome stems from three key factors:

- Automated Coordination: AI increasingly handles routine coordination tasks that previously required human intervention. Large-scale ERP deployments show this duality—while machine learning document review cuts legal coordination costs by 37%, the most significant gains come when small teams leverage these capabilities without the bureaucratic overhead of large organizations.

- Knowledge Amplification: AI tools dramatically enhance individual capabilities, allowing small teams to access specialized expertise on demand. Research on AI-driven scaling demonstrates how LLMs automate traditional growth bottlenecks—customer support (Intercom), content creation (Jasper), and coding (GitHub Copilot)—allowing 10-person teams to achieve what previously required 100-person departments.

- Proximity Advantage: Small teams maintain the critical proximity to value we explored earlier. While both large and small organizations can access AI tools, smaller teams integrate these capabilities directly into value creation rather than through multiple abstraction layers.

Evidence for this shift appears in productivity metrics: early-stage AI-native startups average $1.2M-$1.8M revenue per employee—4-7x higher than traditional software companies at similar stages. This gap widens rather than narrows as these companies grow, suggesting that building with AI from the ground up creates structural advantages that persist through scaling.

The Acceleration of Learning Cycles as Competitive Advantage

The critical competitive differentiator in the AI era isn't data volume or compute resources—it's learning velocity. Organizations that can rapidly absorb information, test hypotheses, and adapt strategies will consistently outperform slower competitors regardless of size.

Three acceleration mechanisms are emerging:

- Experiment Amplification: AI dramatically reduces the cost and time required for experimentation. Teams can simulate numerous scenarios, generate diverse creative options, and test approaches without committing substantial resources. When combined with the shorter feedback loops inherent in small teams, this creates exponential learning advantages.

- Knowledge Integration: Modern AI systems excel at connecting disparate information sources, identifying patterns, and transferring insights across domains. This capability is most powerful in environments with minimal knowledge silos—precisely the advantage that small, aligned teams maintain over compartmentalized organizations.

- Decision Acceleration: By automating data preparation, analysis, and even parts of decision processes, AI compresses what previously took weeks into days or hours. Organizations with streamlined approval processes capitalize on this acceleration, while those requiring extensive consensus remain bound by human coordination bottlenecks.

Research shows this acceleration effect is most pronounced in organizations with fewer than three management layers. Data from 850 companies demonstrates that flatter structures achieve both faster decision cycles and 5.4% higher EBIT margins by reducing the abstraction and coordination costs we identified earlier.

New Organizational Structures Enabled by AI

The combination of AI capabilities and complexity economics is giving rise to entirely new organizational forms optimized for value creation in complex environments:

- Fluid Networks: Rather than static hierarchies, leading organizations are creating dynamic networks where teams form, collaborate, and disband based on value creation opportunities. These structures use AI to manage complexity while preserving human relationships where they matter most.

- Human-AI Complementarity: The most effective structures explicitly design for human-AI collaboration rather than treating AI as merely a tool. This includes creating roles focused on prompt engineering, AI output validation, and integration of AI-generated insights with human judgment.

- Augmented Proximity: Digital twins, AR workflows, and blockchain oracles provide technological bridges that maintain proximity to value even at scale. For example, GE's wind farm simulations update in real-time based on turbine sensor data, allowing engineers to test abstract control algorithms against physical performance without losing context.

These new structures operationalize what economist Ronald Coase theorized decades ago: that the boundary of the firm is determined by the point at which transaction costs of market coordination exceed bureaucratic costs of internal coordination. AI fundamentally shifts this equation by dramatically reducing certain types of coordination costs while enabling new forms of collaboration.

Managing AI's Complexity Paradox

While AI offers powerful tools for managing complexity, it also introduces its own form of complexity inflation. Organizations must navigate this paradox deliberately:

- Tool Proliferation: A 2024 survey found that organizations with over 200 AI and collaboration tools experienced 23% longer project cycles than those standardizing on 5-10 platforms. The integration complexity of multiple AI systems can easily outweigh their individual benefits.

- Knowledge Abstraction: AI systems often create additional layers of abstraction between decision-makers and reality. Without careful design, they can amplify the distance problem we identified earlier, creating ever more sophisticated dashboards that further remove leaders from direct value understanding.

- Governance Overhead: Enterprise AI implementations that reduce one form of coordination cost often introduce new ones. While machine learning document review cuts legal coordination costs by 37%, model maintenance requires new cross-functional AI governance teams consuming 15% of IT budgets.

The organizations that thrive will be those that use AI strategically to reduce complexity in high-leverage areas while maintaining human proximity where it matters most. This isn't about wholesale automation but rather about thoughtful augmentation of human capabilities in ways that preserve understanding, context, and connection.

In our final section, we'll explore practical applications of these insights—specific measures organizations can take to measure, manage, and optimize their complexity-to-value ratio in the age of AI and beyond.

8. Practical Applications

Understanding complexity inflation is valuable, but applying these insights requires practical tools and frameworks. This section offers actionable approaches for leaders, teams, and individuals seeking to optimize the relationship between complexity and value.

Measuring Complexity-to-Value Ratio

Before you can manage complexity inflation, you need ways to measure it. Traditional metrics often focus solely on outputs while ignoring coordination costs. A more comprehensive approach combines several measurement tools:

- Productivity Equation: Start with the fundamental relationship we identified earlier:Copy

Productivity = (Individual Output × Team Size) / (Communication Overhead + Coordination Latency)Organizations can operationalize this by tracking metrics like revenue per employee alongside coordination cost indicators like meeting hours, email volume, and decision cycle times. - Coordination Cost Mapping: Conduct periodic audits to quantify resources devoted to coordination versus direct value creation. Research shows coordination costs now consume 18-34% of operational budgets in matrix organizations. Companies exceeding this range typically experience value destruction.

- Distance Metrics: Measure the proximity between decision-makers and value creation using indicators like:

- Steps between customer feedback and product decisions

- Time from market signal to organizational response

- Layers between frontline insights and strategic planning

- Complexity Growth Rate: Track the growth rate of coordination mechanisms (processes, meetings, approval chains) relative to output growth. When the former exceeds the latter, complexity inflation is occurring.

Companies implementing systematic complexity measurement report significant benefits. For instance, Bain's work with a Fortune 500 industrial company demonstrates how measuring and then eliminating 80% of low-contribution SKUs increased operating income by 20% while reducing manufacturing lead times by 15%.

Designing Optimal Team Structures

The structure of teams and their interconnections dramatically impacts complexity-to-value ratios. Several design principles emerge from our analysis:

- Dunbar-Driven Team Sizing: Robin Dunbar's anthropological research identifies 150 as the maximum number of meaningful relationships humans can cognitively sustain. Progressive organizations leverage this finding by:

- Capping autonomous business units at 150 members

- Creating nested team structures following Dunbar's natural groupings (5, 15, 50, 150)

- Redesigning coordination mechanisms when groups exceed these thresholds

- Conway's Law Alignment: Melvin Conway observed that organizations create products that mirror their communication structure. Optimize this relationship by:

- Aligning team boundaries with product/service boundaries

- Minimizing dependencies between teams requiring extensive coordination

- Creating end-to-end ownership of customer journeys

- Value Stream Organization: Structure teams around complete value streams rather than functional specialties. Research shows that cross-functional teams combining diverse cognitive styles (abstract/systemic + concrete/experiential) make 27% fewer errors in complex problem-solving.

- Minimum Viable Hierarchy: Data from 850 companies shows that organizations with three or fewer management layers achieve 5.4% higher EBIT margins than hierarchical peers. Flatter structures maintain proximity to value while minimizing coordination overhead.

Spotify's squad model exemplifies these principles through nested teams: squads (≤8 members) focusing on specific microservices, tribes (≤150 members) aligning related squads, and guilds/chapters maintaining expertise networks while preserving autonomy. This structure reduces cross-team dependencies by 64% compared to traditional hierarchies.

Tools for Complexity Reduction

Beyond measurement and structure, specific tools can systematically reduce complexity without sacrificing capabilities:

- Process Rationalization: Apply the "Drain-Make-Fix" approach used by high-performing organizations:Companies instituting quarterly process reviews achieve 28% higher EBITDA margins than peers.

- Drain: Eliminate redundant or low-value processes through regular audits

- Make: Create streamlined processes that preserve value while reducing coordination

- Fix: Continuously improve remaining processes based on frontline feedback

- Decision Protocol Optimization: Establish clear protocols for different decision types:Organizations implementing tiered decision protocols reduce decision latency by 62% while maintaining or improving decision quality.

- Type 1 (irreversible) decisions require thorough analysis and broader input

- Type 2 (reversible) decisions should be pushed to the lowest appropriate level

- Automate recurring decisions through algorithms and clear guidelines

- Automation-Enhanced Workflows: Strategically apply automation to coordination bottlenecks:Research shows teams using AI to handle routine coordination tasks recover 7-10 hours per person weekly for direct value creation.

- AI-powered meeting summarization and action tracking

- Workflow systems that route approvals only when necessary

- Knowledge management tools that reduce redundant information seeking

- Technology Portfolio Rationalization: Avoid tool proliferation that creates integration complexity:A 2024 survey found that organizations with streamlined technology portfolios experienced 23% shorter project cycles than those managing hundreds of disparate systems.

- Standardize on 5-10 core platforms rather than hundreds of specialized tools

- Prioritize deep integration between fewer systems over shallow connections between many

- Regularly audit and remove underutilized or redundant technologies

Individual Strategies for Complexity Management

While organizational approaches are powerful, individuals can also employ strategies to navigate complexity effectively:

- Proximity Preservation: Deliberately maintain direct contact with value creation:

- Regularly engage with customers or end-users regardless of role

- Practice "management by walking around" to absorb contextual information

- Complement data analysis with direct observation

- Attention Protection: Guard against context-switching costs:

- Block focused work time for deep, value-creating tasks

- Batch coordination activities (email, meetings) into dedicated time blocks

- Use the "two-minute rule" to immediately handle quick coordination tasks

- Complexity Contributions Awareness: Recognize your role in organizational complexity:

- Before creating a new process, calculate its coordination costs against benefits

- Question whether meetings and reports actually serve value creation

- Suggest simplification of overly complex procedures

These individual approaches, when adopted widely, can create cultural shifts that naturally counteract complexity inflation. Organizations with cultures explicitly valuing simplicity show 24% higher innovation rates and 31% better employee retention than complexity-tolerant peers.

By combining organizational systems with individual mindset shifts, it's possible to create environments that capture the benefits of scale and specialization without succumbing to the coordination costs that typically accompany growth. In our final section, we'll look toward the future of complexity management and draw conclusions about the path forward.

9. Conclusion: The Future of Value Creation in a Complexity-Aware Economy

Complexity inflation isn't merely an organizational challenge—it's a fundamental economic force that shapes businesses, markets, and innovation itself. Throughout this exploration, we've seen how the natural tension between scaling and value creation manifests across various contexts, from startup lifecycles to AI implementation.

The central insight remains consistent: as systems grow more complex, the coordination costs eventually outpace the value created unless deliberately managed. This isn't a bug but a feature of human cognitive architecture and network mathematics. Understanding this reality gives us both the framework to diagnose organizational dysfunction and the tools to design better systems.

The Dual Transformation Challenge

As we look to the future, organizations face what I call the "dual transformation challenge"—simultaneously optimizing current operations while developing next-generation models that transcend existing complexity constraints. As Reid Hoffman notes, "The companies that blitzscale today will be those that can simultaneously optimize for efficiency and experimentation."

This dual transformation will require:

- Rethinking Organizational Boundaries: Rather than monolithic corporations, we'll see more fluid networks of smaller, purpose-driven teams that form, collaborate, and reconfigure as needed. The boundaries between companies will blur as transaction costs fall and value networks replace traditional supply chains.

- Reimagining Coordination Mechanisms: AI will increasingly handle routine coordination while humans focus on high-judgment, high-creativity work. The organizations that thrive will be those that design these human-AI partnerships intentionally rather than layering technology onto existing hierarchies.

- Rebalancing Proximity and Scale: The fundamental trade-off between closeness to value and organizational size will remain, but technology will create new possibilities for maintaining connection even at scale. Digital twins, immersive technologies, and semantic networks will provide powerful bridges across distance.

Practical Steps Forward

For leaders navigating this transition, several immediate actions can yield outsized returns:

- Measure Your Complexity-to-Value Ratio: Begin tracking coordination costs alongside traditional output metrics. Understanding this relationship is the essential first step toward optimization.

- Implement Regular Complexity Audits: Just as financial audits prevent waste, complexity audits can identify and eliminate unnecessary coordination mechanisms before they become entrenched.

- Redesign Around Human Cognitive Limits: Use Dunbar's number and other cognitive insights to structure teams that naturally minimize coordination overhead while maximizing understanding.

- Invest in Proximity-Preserving Technology: Prioritize tools that bridge distance without adding abstraction layers—those that bring decision-makers closer to value rather than further away.

The Opportunity Ahead

While complexity inflation presents significant challenges, it also creates extraordinary opportunities for organizations willing to innovate in their fundamental design. The gap between theoretical best practices and typical organizational structures remains enormous, suggesting substantial untapped potential.

Just as the industrial revolution required new organizational forms (the modern corporation, functional departments, management hierarchies), today's technological revolution demands fresh approaches to coordination and value creation. The organizations that develop these approaches first will enjoy significant competitive advantages.

The economics of complexity isn't just a constraint—it's an invitation to reimagine how we create value together. By understanding how complexity grows, how proximity drives understanding, and how relationships can be structured for maximum value, we can build organizations that achieve what previously seemed impossible: combining the agility of small teams with the capabilities of large enterprises.

In a world where complexity continues to increase, the ability to manage it effectively may be the defining competitive advantage of our time. The future belongs to those who can create maximum value with minimum complexity—not by avoiding complexity entirely, but by designing systems where complexity serves human understanding rather than obscuring it.

Bibliography

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for "lemons": Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488-500.

Balfour, B. (2019). The traction-transition-growth trichotomy in startup development. OpenVC. https://www.openvc.app/blog/startup-lifecycle

Bain & Company. (2022). The power of managing complexity. https://www.bain.com/insights/the-power-of-managing-complexity/

Bar-Yam, Y. (2004). Making things work: Solving complex problems in a complex world. Knowledge Press.

Blank, S. (2013). The four steps to the epiphany: Successful strategies for products that win. K&S Ranch.

Brooks, F. P. (1975). The mythical man-month: Essays on software engineering. Addison-Wesley.

Brown, M. (2020). Five-stage progression in startup development. Learn MARSD. https://learn.marsdd.com/article/revenue-per-employee/

Chen, K. (2025). Extensions of Bertrand competition models in differentiated markets. Journal of Economic Theory, 192, 105-128.

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469-493.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519-530.

Hoffman, R. (2018). Blitzscaling: The lightning-fast path to building massively valuable companies. Currency.

Hrebiniak, L. G., & Joyce, W. F. (1984). Implementing strategy: An appraisal and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 202-213.

Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(1), 1-47.

McMartin, S., et al. (2023). Meta-analysis of scaling studies: Productivity gains and efficiency losses. Strategic Management Journal, 44(3), 547-568.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. University of Chicago Press.

Schrage, M., et al. (2021). Understanding proximity advantage in decision-making. MIT Sloan Management Review, 62(4), 81-89.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440-463.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. Free Press.